Theory

In episode 1-8 The Bones Go Home, I said that "a verse of the New Testament is like a first-century soundbite. We find a pithy sentiment and then isolate and latch on to it, but there is always a context and a message surrounding the one or two sentences that we adore so greatly." Culling a handful of verses here and there is a sure way to miss the big picture that Stories of Symmetry strives to reveal. Not that there's ill intent, necessarily, but incompleteness.

If you've read my book Practical Advice for a Better World, then you know I tackle issues of societal organization. One of the topics I am asked about is socialism, particularly in response to the early church's supposed adoption of that philosophy, as recorded in Acts 2:44-45: "All the believers were together and had everything in common. They sold property and possessions to give to anyone who had need."

Is this socialism? Well, what is socialism, anyway? Reductively, it's systems of social ownership wherein members of the company/party/country/etc. are "owners", not merely employees/members/citizens/etc. The prevailing motivations behind most socialist organizations are stability and fairness—though social ownership, of course, guarantees neither of these.

Socialism is different from communism (government controls everything and there's no private property), anti-capitalism (opposition to letting people have choice regarding purchases), egalitarianism (all personal outcomes are equal because there is no social organization or specialization), and other associated philosophies. Additionally, while socialism can be targeted at various levels of government, it is not strictly political.

In a pure sense, the early church may well have been socialist, because presumably there were no "owners" other than the collective membership itself. Although people like Simon Peter, Mary Magdalene, Paul, and many other disciples held leadership roles, they probably didn’t regard themselves as the church's masters.

In the same way, the Presbyterian church might be regarded as socialist, since it is congregation-led. And since the Presbyterian model is the basis for representative democracy (such as the United States and many other countries use), perhaps the U.S. should be considered socialist—again, in a pure sense, no politics intended.

Factors

However, we know that many philosophies are not discussed in pure senses, so it's important to distinguish what we know about the early church from what is often associated with socialism. There are two factors worth mentioning:

Intent. If the early church was socialist, it was not because a few organizers wanted to control others and their outcomes. Rather, it was because each individual member chose to place Jesus above everything else and model his self-sacrifice, minimalism, and rejection of wealth for the sake of wealth. This is altogether opposite from leaders instantiating a socialist façade while simultaneously stockpiling resources and power for themselves.

Second, willingness. All participants were voluntary and able to come, go, and participate at their discretion. Furthermore, as the congregations were comprised by both rich and poor, salve and free, etc., we know that the church did not authoritatively impose on personal lives or livelihoods.

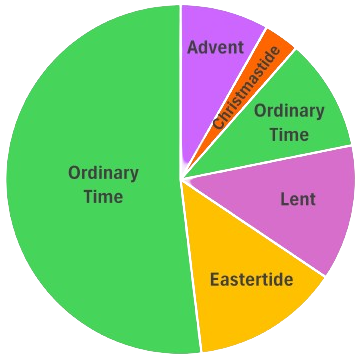

Pragmatically, this makes sense, because socialism's effectiveness is strongly correlated to relationships, virtue, and willingness. This is why socialism is tenable at small scales, but ineffective at large scales. (Keep in mind that supposed socialist countries like the oft-cited Scandinavian ones are not actually socialist, but redistributive capitalist; others, such as some East Asian countries, are actually communist.) When you don't know the people your self-sacrifice is supposed to help (lack of relationships), there are enough bad apples to spoil the bunch (lack of virtue), and people are forced to participate (lack of willingness), the system crumbles.

Conclusion

Socialism is a system of ownership. It does not, of its own accord, lead to fair or good outcomes; neither does it have an opinion on wealth, politics, religion, welfare, the environment, or anything else often associated with it. In fact, socialism and democracy, even socialism and capitalism, often go hand-in-hand. Socialism is a little bit like a Rorschach test; what you say about it reflects you, not the thing itself.

Therefore although it is possible (though not proved) that the early church thrived on a socialist system, it is probably unwise to boldly make that claim because of society's misunderstanding of socialism itself. It’s analogous to discrimination. Discrimination, in a pure sense, is not bad. It's synonymous with sorting, and sorting is morally and ethically neutral. Of course, when people think about discrimination, they think about demographic discrimination for unjust purposes… so I would caution the reader against loudly proclaiming the merits of discrimination (in its pure sense).

Better than ask about socialism, we should ask about the character of the early church. It was dedicated to Jesus's teachings. As such, it rejected the world's evil from whatever system it arises. It did not despise unjust people, only their unjust ways; it did not reject wealth, but the claim that it is life's greatest goal; it did not reject privacy nor private anything, only the use of those to conceal wrongdoings.

Lastly, and more importantly, is what the church did. It held fast to Jesus. It loved the marginalized and needy. It sought to be fair. It sought to understand. These are what we should emulate. Regardless of the infrastructure that supports it, we should remember the mission and carry it forward.

This blog is about "was the early church socialist?", "what is socialism?", "what should we emulate about the early church?" Acts 2:44-45.

Symmetry

Symmetry